Photo by by Elodie Olson-Coons

The Danube is many things at once. During our two-week journey on the M.S. Fusion, we cross the following borders: Hungary/Serbia, Serbia/Croatia, Croatia/Serbia. The stamps on our passports are black and white, neat Cyrillic rectangles. Enter/exit.

But the reality of those crossings is much more ambiguous. The Liquid Becomings crew – five artists, two curators, one captain – officially departs Hungary at the port border crossing in Mohács, ten kilometres before crossing the map-drawn border line into Serbia, and hours before we get our passports stamped upon arrival in Apatin, floating in the ambiguous space of this international waterway. In the final days of our trip, in an emergency situation due to high winds and a failing motor, we dock on Romanian soil without technically entering Romania (though with plenty of paperwork).

On the Danube, the deeply theoretical and imaginary nature of these borders is all around you: there is nothing to see but water and shore. The late-summer heatwave sun beats down everywhere equally. Even the shipping channel wanders back and forth, closer to one body of land or the other. Traffic and border police boats go more or less where they want to. There’s no barbed wire here, no watchtowers, which doesn’t mean these borders aren’t closely patrolled, or dangerous.

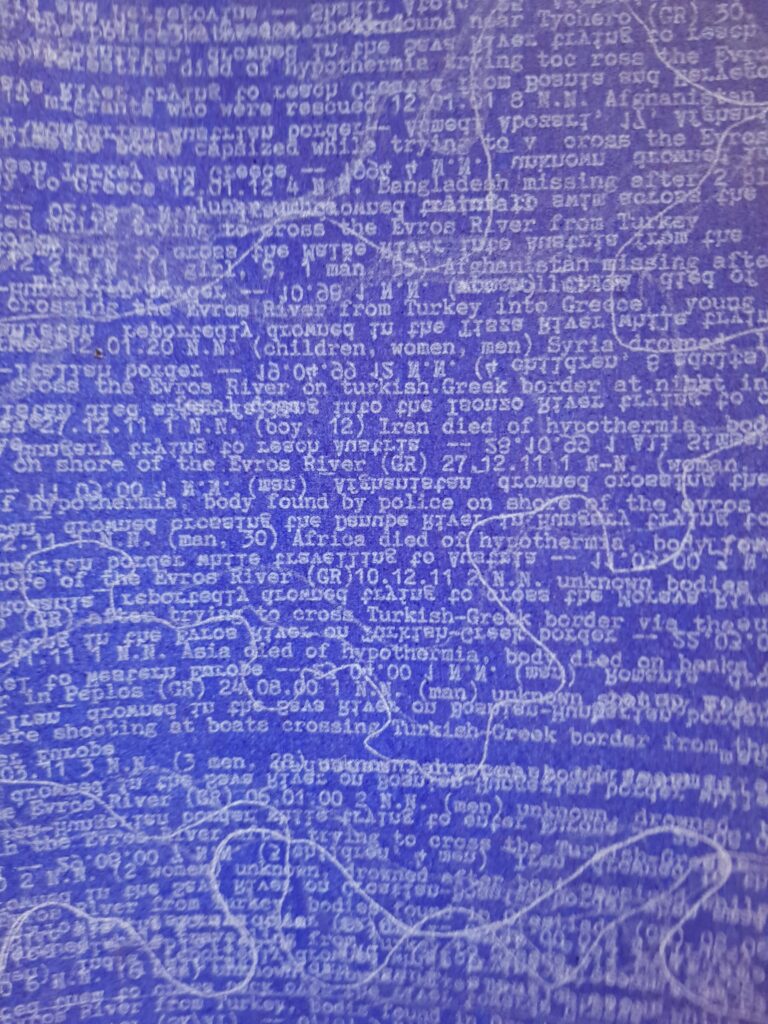

Three men from Congo were found dead near the Kupa river in Severin na Kupi, in Croatia. A twenty-year-old man from Afghanistan was shot in a rubber boat by Croatian police as he was attempting to cross the Sava from the Bosnian side. A ten-year-old girl from Turkey drowned after falling from her mother’s shoulders while crossing the Dragonja river from Croatia to Slovenia. Six people, including two children, drowned after their boat capsized in the Danube at Karabukovo while trying to cross from Serbia into Croatia. Four are still missing.

All across the Balkans, river borders just like this one are claiming lives. Almost a year ago, I first came across the UNITED List of Refugee Deaths, and started to understand just how deadly these external EU borders are for people on the move: not just the Mediterranean, not just the forests and the roads, but the rivers, too. Malse, Morava, Rezovo, Dobra, Reka, Isonzo, Vukovci, Danube, Tisza, Drina, Glina, Nisava, Una, Korana, Dragonja, Maritsa, Mrežnica, Kupa, Evros, Sava: for many, these beautiful names of rivers across the Balkans spell nothing but death.

Once you read the stories – a single, truncated glimpse into the end of these journeys, these lives – it’s impossible to look away. I started researching the question during a four-month residency in Belgrade at the start of this year, conducting interviews with activists, academics and government workers, speaking to NGOs, and simply spending time in these fluid spaces, trying to parse their ambiguity, trying to understand how they work.

The journey this September with Liquid Becomings was another way of coming into direct contact with the Danube, one of the major river borders into Europe: a contested border in several places, a waterway that meanders from the heart of the EU to its furthest margins. History is deeply layered here, from the deepest layers of Pleistocene sand to traces of iron oxide from Neolithic pottery. Right-wing graffiti on plaster over shrapnel marks. Empty water bottles in the river mud.

The Danube, too, is a conflicted and contradictory space, full of industrial machinery and wild islands, a junkyard and an ecosystem all at once. On its edges, sharp loess cliffs and endless green flatlands. I’m interested in the intersections between these layers and how they shape the region as a liminal space on the edge of the EU. After all, border rivers are no more dangerous than any other body of water. It is our own philosophies and technologies of bordering, our exclusionary and racist migration policies, our blind eye turned to abuses of power that are killing people.

At the end of the journey, back on dry land, the work is not done. I am still actively collecting testimonies from people who have made the crossing. Sorting through my field recordings. Writing up. From time to time I still feel the lilt of the river beneath my feet. Bright and murky waters.

Text by Elodie Olson-Coons, writer and artists working with text, part of the Danube crew of Liquid Becomings – Pavilion 2024

*This text is part of Notes from the rivers, a series of reflections from people that are taking part in, are connected to or are very sympathetic to the European Pavilion 2024: Liquid Becomings and the discussions being posed by the project. Each text expresses the personal ideas and positioning of the authors.