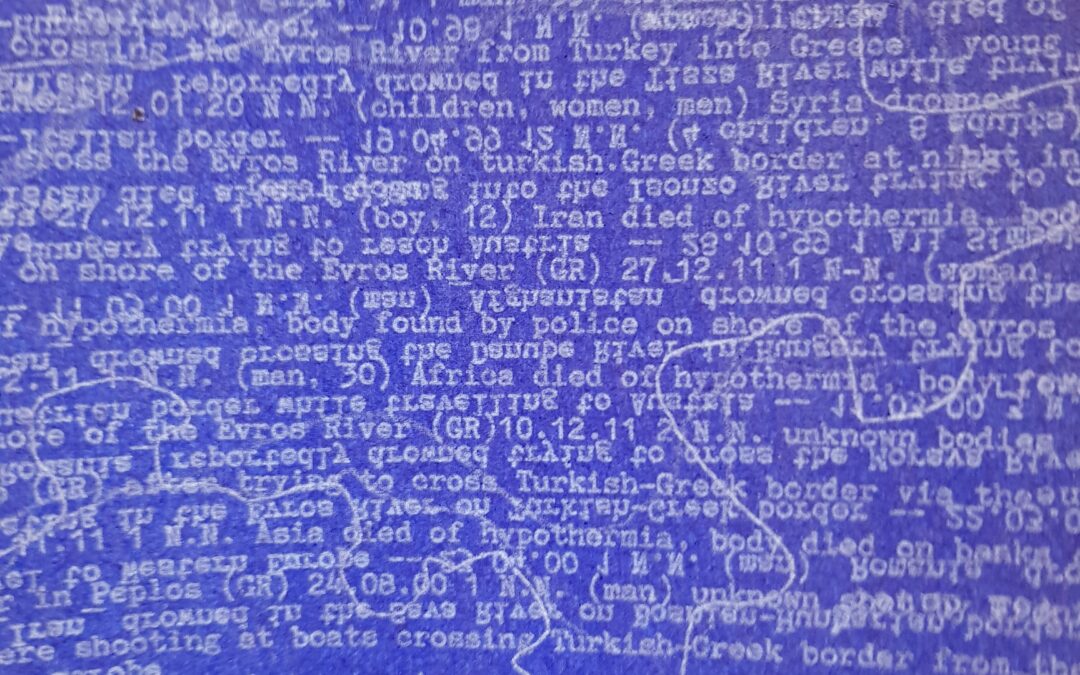

Photo by Marta Niedbal

Public Spaces, Common grounds, Fediverse: the next round of collective action around public spaces

‘Public Spaces’ is a perpetual feel-good word, certainly in progressive circles. In broad strokes, ‘public spaces’ pertain to the territories and spaces – physically, metaphorically – which should belong to us all. Intellectually and practically, conversations around public spaces invite us to reflect about our ‘common ground’ or ‘common goods’, and ‘commonality’. During chaotic foundational times such as we live again today, conversations about public spaces often abound. To articulate what constitutes our renewed ‘commonality’ is a core question in times of deeper change.

We spoke about today’s struggles around public spaces with Marleen Stikker, director of de Waag, Futurelab for Technology and Society in Amsterdam. Marleen is very active in PublicSpaces, a coalition of public organizations from public broadcasters, heritage institutions, festivals, libraries, museums and education, which work together to find creative solutions to a major shared concern: how to deal with today’s world dependence on big tech shaping our public sphere?

Many recent publications address shifts in configuration of our public space caused by the arrival of the internet and later social media. Marleen Stikker has been immersed in many of these issues since the 1990s, which she related in vivid detail in her 2019 book: Het internet is stuk. Maar we kunnen het repareren (The Internet is broken, but we can repair it).

The text below brings together some of the many interesting points that Marleen Stikker shared for the Liquid Becomings blog Notes from the river.

“The arrival of the internet back in the 1980s as a facilitator of new public space felt like a ‘greenfield’. Early adapters at the time included hosts of creative people, designers, people in social movements, hackers. They loved technology as man-made, explorative, creative. They saw the emerging technologies and the internet as a new public space in which people could actively and more democratically engage. One manifestation was the Digital City, which we launched in 1994. It was conceived at the time as a public space for citizens and organizations to collaborate. It was there not merely to ‘consume’ things, but to be an active part of developments. People loved it: you could surf the internet, meet people, have discussions, contribute. People immediately saw its potential to connect in new ways.

I was personally interested in the Tcp IP protocol and what it signified: moving to distributive instead of centralized networks…It was a hugely creative time, with many movements springing up: you had PeaceNets, HealthNets, HIV Nets etc., often expanding into larger and larger networks. But already then, you had some divergence between people at the frontlines. Some were totally fascinated by the technology per se, thrilled by the technological potentials, such as many in the Silicon Valley crowd. The European movement was different. Some of us argued even in those early days that the technology, however exciting, was not neutral. We saw that many old questions about power, about who owns the figurations, who writes the protocols, who is in control, were immediately present as well. I think we were not simply optimists, we were realists.

Then in the 1990s, while all kinds of digital options were being explored, the larger political economy of the times kicked in. Politics moved to neoliberal agendas. Notably after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the tone was: capitalism has won the day, the ‘market’ can now do everything. Many of the previously taken-for-granted public services, such as energy, water, health, education, transportation, were transferred to the private sector, not always with public safeguards against the dominant ethos of shareholder-value-first. In the process, the internet itself became pervaded as well. From a ‘greenfield’ in which a lot could be freely explored and codesigned, it turned into a brownfield. I feel sorry for many young people today who now find the internet the way it is and have to carve out new paths to public spaces.

In this climate, we have to mobilize time and again, to articulate the vital need for public space and societal ownership over parts of the technologies and the Internet. Until today. We hammer on the need for transparency and open protocols, on interoperability. We try to salvage the idea that the internet has many potentials to be a public space, with alternative ways to be ruled and organized, and moderated by societal actors.

We use the slogan ‘Taking Back the Internet’. We link to the global discussions about sovereignty and strategic autonomy. We develop practical ways out of the deep dilemmas which organizations today face, such as feeling forced to stay on certain social media they do not necessarily like. We push back on many fronts on the capture of the internet, to create openness and transparency. There are many tools emerging. There are legislative initiatives. We feel there is now an opportunity for companies to launch technologies that have privacy by design, are distributive and interoperable by nature. Some companies do. We feel that that is the future. It is hard work. But with clarity you can change the markets. And legislation can definitely help. We now have Next Cloud, Fediverse. So tools for change are there. We should do things together, it is possible. We can. And yes: we should collectivize!”

Text created from the conversation between Marleen Stikker and Godelieve van Heteren, our board member. The full conversation with Marleen Stikker will also be part of a forthcoming episode of the podcast series Let’s Talk Liquid Becomings.

*This text is part of ‘Notes from the river’, a series of reflections from people that are taking part in, are connected to or are very sympathetic to the European Pavilion 2024: Liquid Becomings and the discussions being posed by the project. Each text expresses the personal ideas and positioning of the authors.